Over the past few weeks a lively discussion has been going on at the Shakespeare noticeboard SHAKSPER under the title “Balcony”. The so-called balcony scene in Romeo and Juliet is probably Shakespeare’s most famous single scene, and no wonder as it’s the one where Romeo and Juliet, at night, passionately declare their love for each other and resolve to marry in spite of the feud between their families.

The discussion on SHAKSPER was triggered by an enquiry from Lois Leveen at the end of February who wondered “why/how the idea of “the balcony scene” developed and proves so persistent in the popular imagination. Why is the balcony so impressed upon the collective consciousness, when no character in the play, and nothing in the stage directions, refers to it as such?”

This was a follow-up comment to remind SHAKSPER contributors of the original question, as responses had gone off at a bit of a tangent, as these things do. For several weeks there have been a variety of posts. Some started discussing arrangements at The Globe, until others pointed out that with the first quarto being published in 1597 Shakespeare didn’t write the play for the Globe, and nobody is sure about the relationship of the second 1599 quarto to the Globe either. Despite evidence of the play’s popularity on stage and in print, there are no records of the play’s performance during Shakespeare’s lifetime.

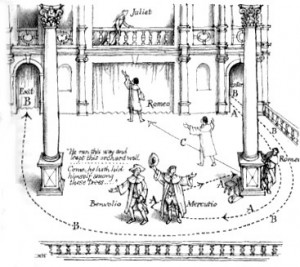

Further posts have suggested a whole series of solutions to the issue of how the balcony scene was staged: a gap in the wall of the tiring house, a stage balcony that might also have been used by musicians, an elevated playing space, a temporary, portable structure, even a descent machine. I have long admired C Walter Hodges’ beautiful illustrations showing how different scenes might have been staged, and this one is for the balcony scene.

Incidentally, there is indeed no stage direction at this point, nor any mention of the word “balcony”. It’s one word that we might have expected Shakespeare to invent, but no. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the first reference to 1618. Almost immediately after the initial enquiry was made Professor Peter Holland came up with a great response to at least part of it, suggesting that the balcony, as a stage direction in Romeo and Juliet, is “first used in Thomas Otway’s adaptation, The History and Fall of Caius Marius (1680), p.18, in the marginal stage-direction “Lavinia in the Balcony.”

Looking at the source of the play, Brooke’s 1562 poem Romeus and Juliet, Brooke too has Juliet appearing at her window:

Impacient of her woe, she hapt to leane one night

Within her window, and anon the Moone did shine so bright

That she espyde her love.

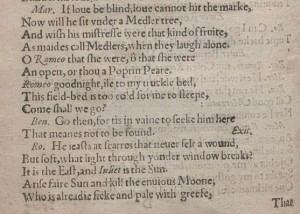

There’s another little curiosity regarding the scene: at some point in the history of editing, the Balcony scene has been divided up from Act 2 Scene 1 and called Act 2 Scene 2. Looking at the illustration of the second quarto text from 1599, it’s clear that Shakespeare conceived it as a continuation, and that this is how it was performed (and still is). With no stage direction, Romeo says “But soft, what light from yonder window breaks? / It is the east, and Juliet is the sun”. The RSC edition is one of few that prints the scene all in one.

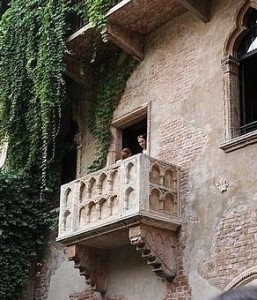

As Lois Leveen suggested, the balcony scene has entered the collective consciousness, so much that a balcony in Verona has become the centre of a kind of Juliet cult.

This website acknowledges that “the two main characters never really existed and William Shakespeare never went to Verona”, but :

Juliet’s house (Casa di Giulietta) is one of the main attractions of Verona with the most famous balcony in the world. Every day crowds of people make their way through the narrow archway into the courtyard to admire and photograph the famous balcony. Couples of all ages swear eternal fidelity here in memory of Shakespeare’s play “Romeo and Juliet”.

Apparently, because of the demands of tourists to see the place where the action of the play really happened,

the city of Verona bought today’s house of Juliet from the Dal Capello family in 1905. Due to the similarity of their names they declared the house to be the family residence of the Capuleti family – a new tourist sensation was created!

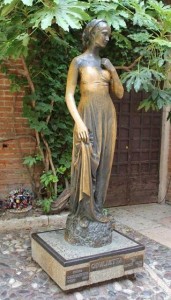

Those who enter the courtyard of Juliet’s house for the first time will be struck by the thousands of small scraps of paper which cover the floor to the ceiling. All who write down their love vows to their partner and stick them on the wall will – according to the popular belief – stay together with their partner for the rest of their lives and will be very happy. Even touching the right breast of the bronze statue of Juliet in the small courtyard will bring luck to all who are trying to find their true love.

I visited the site a few years ago the walls were covered in graffiti. I gather than in recent years they removed the graffiti and now have hung panels on the wall onto which messages are allowed, though it sounds as if messages are still written on scraps of paper and stuck on with chewing gum.

In addition The Juliet Club receives over 6000 letters a year addressed to Juliet in Verona from heartbroken or lonely people (mostly girls). Each is individually answered, and the letters are kept in a special archive. A strange phenomenon, and testament to the power of Shakespeare’s romantic tragedy.

You mention: “This website acknowledges that the two main characters never really existed and William Shakespeare never went to Verona.”

However there appears to be an inconsistency in that position, in that none of the sources for the author’s text note, and I am quoting the Romeo and Juliet words here, “underneath the grove of sycamore/ That westward rooteth from the city’s side”. This sycamore grove is still visible through the Porta Palio. Whoever wrote the play knew about it and mentioned it in a natural and familiar way.

Thus it is questionable to categorically state that “William Shakespeare never went to Verona.”

Similarly, the “St. Peter’s Church” is the San Pietro Incarnario and is still where Juliet’s parish was, was a parish church in that era, and is and was directly on the path between her house and the residence of her confessor, Friar Laurence in the play, at his (then) Franciscan monastery. According to the author Richard Paul Roe, after many changes and damages, it is now “a simple meeting hall.”

It was never mentioned in the literary background upon which the author relied. Thus we are faced with whether he knew about it from precise and remembered personal experience. Contrary to the recently manufactured concept that Shakespeare is all imagination, it was his fidelity to truth that contributes to the compelling nature of his art.

Thanks for your comment. The line you highlight is a quote from the Veronese website, but in spite of attempts to suggest that Shakespeare travelled to Italy there is no evidence he ever did so.

Well written and ultimately touching blog entry – BTW – have you seen the movie Letters from Juliet – set in Verona, it deals with The Juliet Club – is a bit contrived, but the meeting of Vanessa Redgrave and the love she has been looking for – Franco Nero – is one of the most moving scenes I have ever seen in a movie.

Thanks for your comment and the information about the film Letters from Juliet which I have heard of, but not seen.